Norman Rockwell - Painting a Sports Art Masterpiece

The Famous Artist Was Ahead of His Time In How He Composed His Artworks

Intro

In Part 1 of this article, we took a look at some of Norman Rockwell’s most well-known artworks that featured a sports theme. To recap briefly, Rockwell envisioned himself not just a painter but a storyteller, creating works with a cinematic style and a sense of humanity that made them relatable to the American public of his time. In fact, the moments Rockwell captured in his work became such a part of the country’s visual identity that the phrase “Norman Rockwell Moment” came to be used to describe small-town events and rites of passage.

When I began to look into how Rockwell created his works I found a deeper appreciation of him and his art. And in the process, I discovered more about why such legends as film directors Steven Spielberg and George Lucas have praised Rockwell not only for his painting ability but for his prowess as a storyteller. Two methods that Rockwell employed as a storyteller were his unorthodox uses of photography and models.

How Rockwell Used Photography As Reference

The book “Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera” reveals how Rockwell used photography, in a manner ahead of his time, as a reference for his works. What set Rockwell apart from most artists at that time was that he rarely used a single photograph as a reference but would cobble together multiple reference photos so that he could create a perfected image to paint. Using black and white photos, which allowed Rockwell a sense of freedom in defining the color palette of the finished painting, he would combine different photos of each piece of a painting, often down to separate images for individual figures, props or details.

Throughout his career Rockwell employed photographers who would work alongside him to capture reference images that fit his needs as he composed his works. Rockwell’s use of reference photos was so meticulous that he sometimes captured as many as one hundred photos for one painting and his archive houses some 18,000 negatives.

Kreindler on Rockwell

I asked noted sports artist Graig Kreindler, himself a Rockwell fan, about Rockwell’s use of photography. “In his world, he was making his own reference to suit his needs—whatever it was that worked best for the picture, that told the story better—was what he was after. So in that sense, he was the main architect and was rarely limited by what he used as a reference. If something wasn’t working right, he could easily reshoot a scene or model and adjust accordingly.” Kriendler noted that this differed from his own use of reference photography, which typically involves a photograph of a famous athlete or a famous moment in sports, rather than a perfected moment à la a Rockwell Moment. “When it comes to my own work, I only wish I could be that way. Normally, I find myself a bit handcuffed by the reference that I use, being that it’s all found and not really made up. And because I’m so anal about the historical accuracy, I have a really hard time taking license.”

If something wasn’t working right, he could easily reshoot a scene or model and adjust accordingly. - Graig Kreindler

But all of these reference photos would matter little if not for the models Rockwell used and how he used them. Instead of professional models, Rockwell preferred to use everyday people, often friends and neighbors, as subjects for his works. Rockwell felt that this allowed him to get more authentic expressions from more “real” looking people. Working much like a film or theatre director, Rockwell would direct his models through various poses and expressions, all of them captured by his photographer for possible use.

In the late 1960s, Rockwell began doing more artwork for advertising and licensing purposes in addition to his work for Look and other magazines of the day. One of these advertising pieces provided a unique glimpse into Rockwell’s creative process.

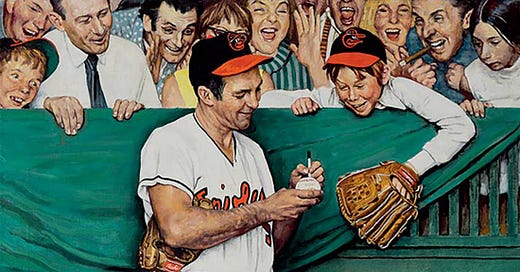

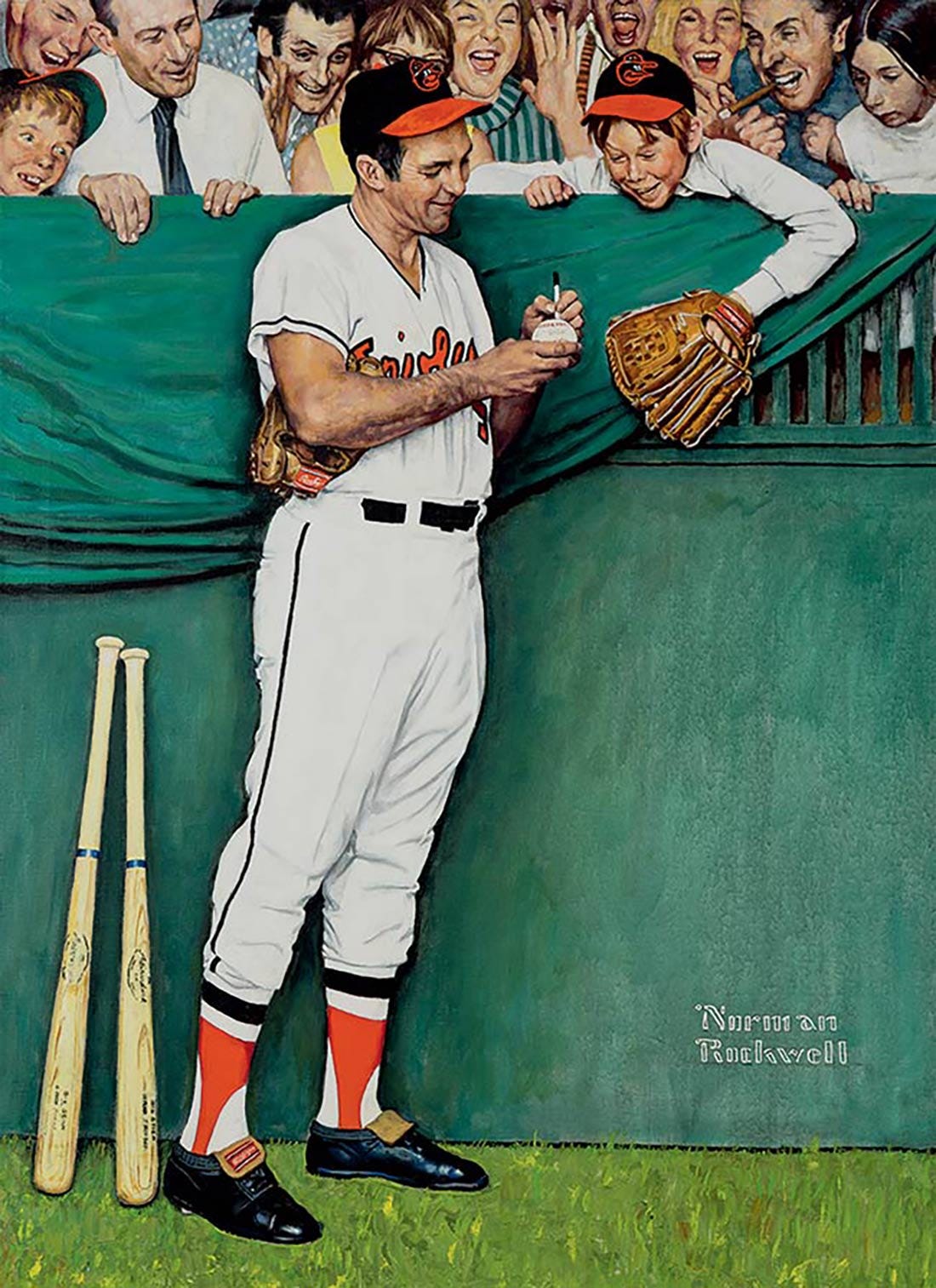

Gee, Thanks Brooks

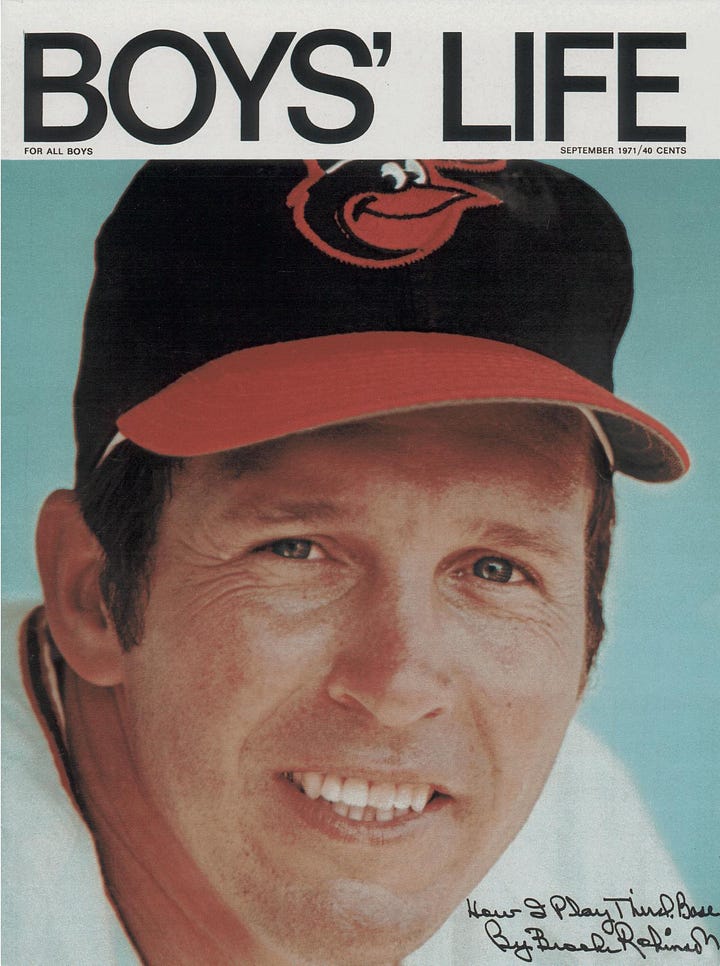

In 1971 Rockwell painted “Gee, Thanks Brooks” to be featured in an ad for ATO, at the time the parent company of Rawlings and Adirondack baseball equipment brands. The painting depicts a young boy leaning over the stands to get an autograph from Orioles third baseman Brooks Robinson, who was just a few months removed from his amazing performance in the 1970 World Series.

The ad debuted in the September 1971 issue of Boys’ Life magazine, somewhat of a Brooks Robinson issue, with Robinson on the cover, in a 4-page article and featured in several ads. The piece is a bit atypical of Rockwell’s sports art in that it depicts a famous athlete as the focal point of the piece, not merely as a bystander or background element as with his earlier works. Given that the piece was commissioned for an advertisement this is easily understood, although it still can be argued that Rockwell has created another of his Norman Rockwell Moments in that Robinson is not depicted in baseball action but rather giving an adoring fan an autograph - something that countless young fans of that day could no doubt relate to.

Memories Of A Rockwell Model

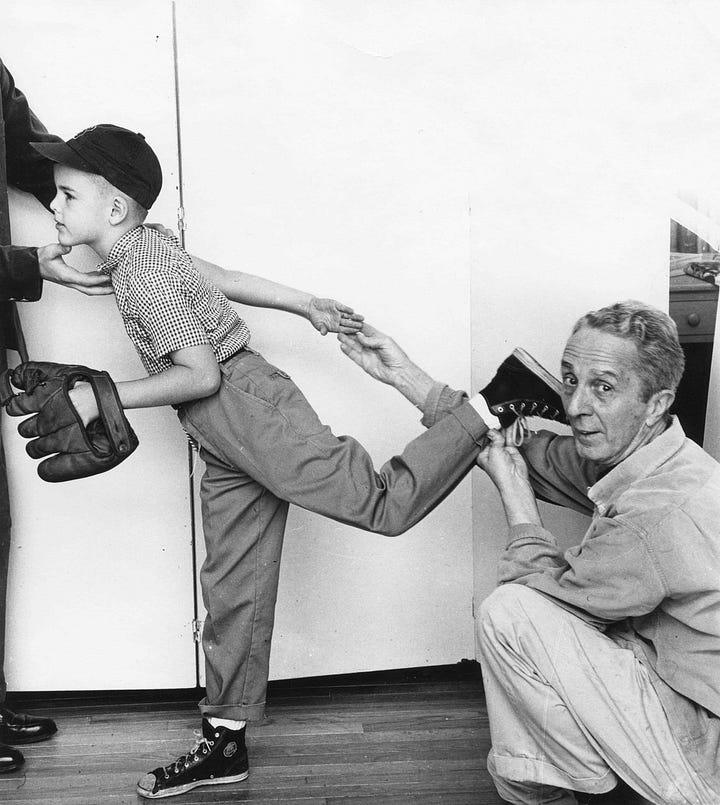

The young autograph seeker depicted in the painting is Hank Bergmans, who at the time lived near Rockwell in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Also appearing in the piece are Bergman’s father, mother, and sister. I was fortunate to speak with Mr. Bergmans who offered first-hand experience of Rockwell’s process and what it was like inside the artist’s studio.

“Around that time (1969 - 1974), I was a go-to model for Norman Rockwell. I’d get taken out of class and walk to the studio to pose for some photos. When I found out I was gonna pose with Brooks, I went digging in my baseball cards but all I could find was Frank Robinson’s card. It must have been a Saturday, to get us all there at the same time.”

I asked if he had any recollections about posing for that particular image. “Brooks was a righty but signs with his left hand. I’m also a lefty but posed as a righty. It was all about the orientation of Brooks and I, I guess. Plus Rawlings provided the glove, and they didn’t ask. Norman always made sure our expressions were bigger than normal.”

Bergmans said being in Rockwell’s studio was very fun. “He had a lot of cool stuff in there, props and things he collected over many years. Never really took a long time - set up, instructions, Louie (Lamone, Rockwell’s photographer in Stockbridge) taking several shots with his large format camera and that was usually it.

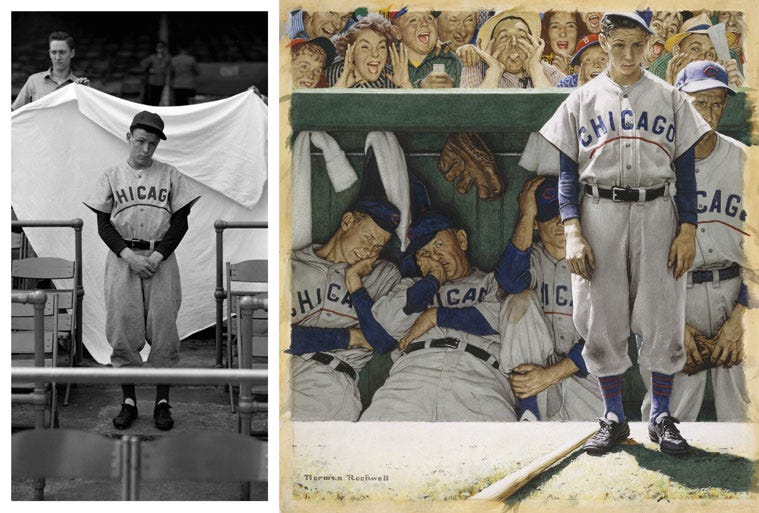

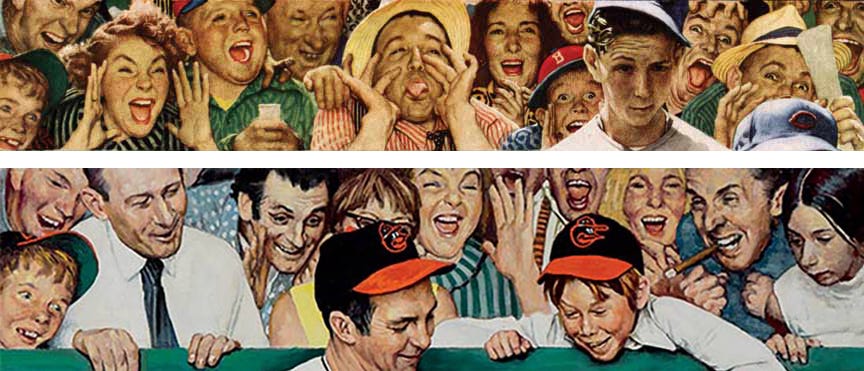

Bergmans also pointed out that Rockwell used a bit of artistic recycling to fill out the crowd beyond his family. A close comparison to 1948’s “The Dugout” shows that the artist used several fans from the earlier work again, including the boy in a baseball cap (lower left), the screaming girl with hands outstretched (who moves from far left in “The Dugout” to the right side of Robinson) and Rockwell himself, who goes from far left to far right and adds a cigar in his mouth. Also in the crowd is Rockwell photographer Louie Lamone (in the polka dot shirt next to Mr. Bergmans).

Norman Rockwell’s artistic talents and attention to detail enabled him to create works of art that are still celebrated and cherished almost 50 years after his passing. Whether depicting professional athletes or sandlot youngsters, his works conveyed the humanity that exists in sports and shed an artistic light on those moments when humanity is displayed.

I would like to thank Graig Kreindler and Hank Bergmans for taking the time to offer insights and recollections for this piece.

A version of this article previously appeared on Uni Watch. Thanks to UW Editor Phil Hecken for allowing me to republish it here in a slightly different form.

I watched the greatest docent of all time take my two sons — bored out of their minds at the Norman Rockwell Museum after a long day of travel — and tell them stories about the history of another baseball painting. They were no longer bored. It was a master’s class and I will never forget it.

These are great pieces. I’d never seen that Brooks painting. Amazing.